One of the common queries, which I get on the blog is:

I am not a Mathematics / Statistics graduate. Can I still become a good business analyst?

or

I am not good at statistics. Can I still change my career to become a business analyst?

The simple answer to the question is – you can’t become a good analyst until you know statistics. However, you don’t need to be an expert in statistics to become a good business analyst.

So, you don’t need to understand the joke in the strip, in order to qualify as a business analyst:

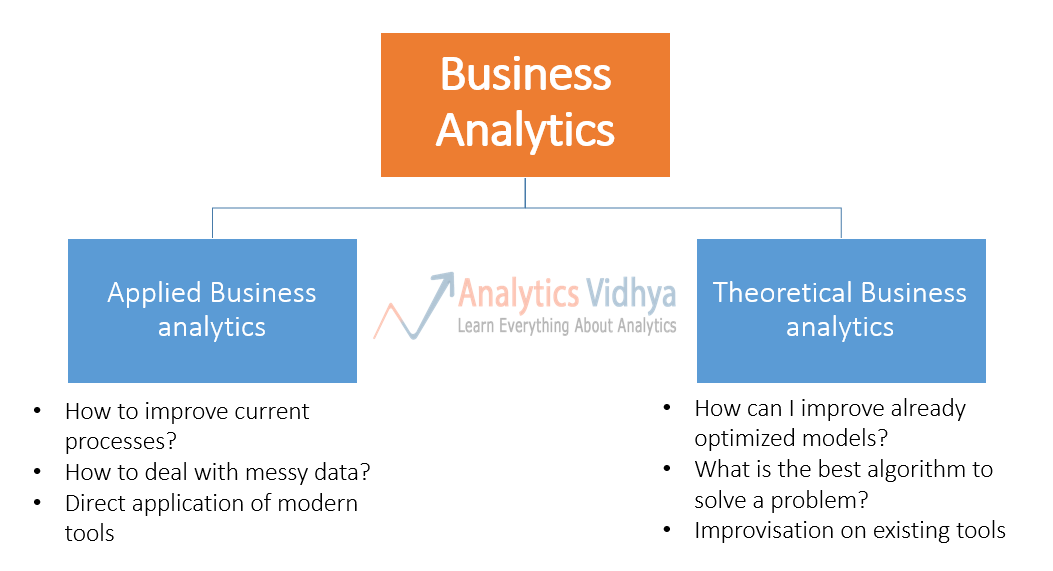

Two types of Business Analytics:

Business anlaytics can be divided in two classes – applied business analytics and theoretical business analytics. Here are definitions of the two streams:

- Applied Business Analytics – This is the work, where the emphasis is to solve a problem at hand. What matters is that you have a strategy / algorithm, which is better than what is happening currently. You deal with practical problems in this stream – messy data, missing values, bad data capture etc. More than 95% of times, you would typically use the algorithm and outputs straight from the tools. As long as you are aware of the assumptions in your model, can check whether they are holding good and interpret the output of the algorithms correctly, you are good for applied business analytics.

- For example, if you know the assumptions in Linear regression and can interpret what is R-square and adjusted R-square, you would be good to apply Linear Regression.

- Theoretical Business Analytics – This is the research area in business analytics. When you have a problem, where current set of algorithms are already optimized and applying standard techniques would not provide you any further uplift. This is when, you need to get into statistical details of various algorithms and then improve them.

Please note that this is not a standard categorization of Business Analytics and it might be difficult to identify some projects in exact buckets. However, it is good enough to communicate the point that you can deal with most of the business analytics problems with basic knowledge of statistics.

What does an analyst need to know?

Now, that you understand the two classes of business analytics, here is some good news! You don’t need to be a statistician to practice applied business analytics.

So, what exactly do you need to know to become an applied business analytics practitioner? I thought why not run a series of articles explaining the basic concepts of statistics, an applied BA practitioner needs to know.

Please note that this series is not intended to be a thesis on statistics. Instead, it takes a very practical outlook to apply statistics to solve business problems.

Concepts to understand population distributions:

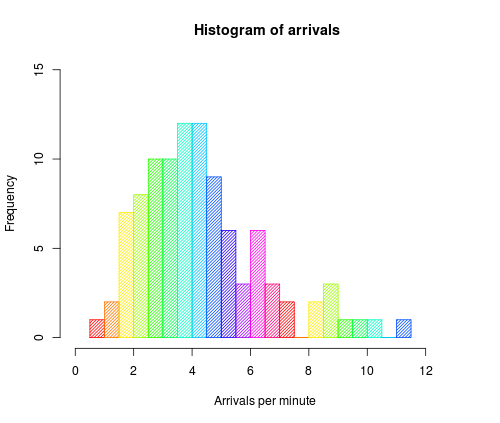

One of the first things a business analyst needs to do is understand various distributions of parameters and population.

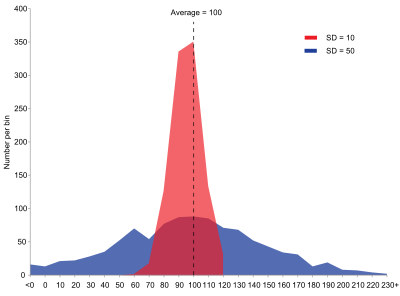

One of the most frequently used method to understand distributions is to plot them using histograms. A histogram represents frequencies of various values through a plot in uniform buckets (popularly known as bins). In case of continuous variables, a histogram represents the probability distribution function (we will cover this later). If you want an example of how histogram is plotted, you can look at this video from Khanacademy. Here is how a typical histogram might look like:

There are 3 variety of measures, required to understand a distribution:

- Measure of Central tendency

- Measure of dispersion

- Measure to describe shape of curve

Measures of Central tendency:

Measures of central tendencies are measures, which help you describe a population, through a single metric. For example, if you were to compare Saving habits of people across various nations, you will compare average Savings rate in each of these nations.

Following are the measures of central tendency:

- Mean – or the average

- Median – the value, which divides the population in two half

- Mode – the most frequent value in a population

The following image illustrates how mean, median and mode would be placed in a couple of scenarios:

Among the three measures, mean is typically affected the most by Outliers (unusually high or low values), followed by the median and mode.

Measures of Dispersion:

Measures of dispersion reveal how is the population distributed around the measures of central tendency.

- Range – Difference in the maximum and minimum value in the population

- Quartiles – Values, which divide the populaiton in 4 equal subsets (typically referred to as first quartile, second quartile and third quartile)

- Inter-quartile range – The difference in third quartile (Q3) and first quartile (Q1). By definition of quartiles, 50% of the population lies in the inter-quartile range.

- Variance: The average of the squared differences from the Mean.

- Standard Deviation: is square root of Variance

Measures to describe shape of distribution:

- Skewness – Skewness is a measure of the asymmetry. Negatively skewed curve has a long left tail and vice versa.

- Kurtosis – Kurtosis is a measure of the “peaked ness”. Distributions with higher peaks have positive kurtosis and vice-versa

A few practical tips to understand distributions better:

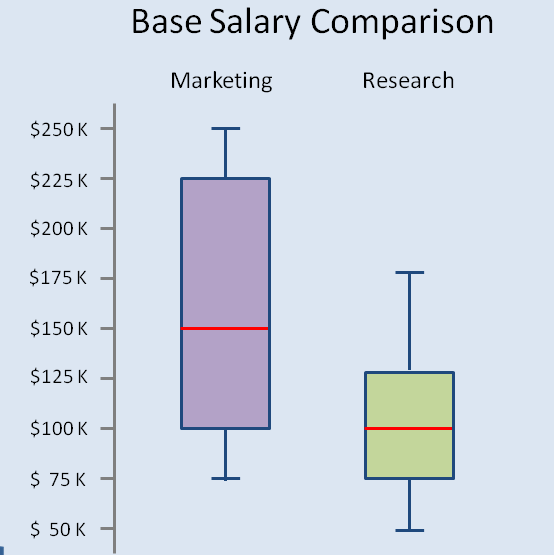

- Use of box plots: Box plots are one of the easiest and most intuitive way to understand distributions. They show mean, median, quartiles and Outliers on single plot.

- You can use box plots next to each other for various categories / segments of population to understand overlap / differences in the population. Following is an example of one such comparison (with illustrative data):

In the article next week (from baby steps in Python series), we will see how to look at these measures and distributions using Python on a Kaggle dataset.