Last week, I saw a recorded talk at NYC Data Science Academy from Owen Zhang, Chief Product Officer at DataRobot. He said, ‘if you are using regression without regularization, you have to be very special!’. I hope you get what a person of his stature referred to. I understood it very well and decided to explore regularization techniques in detail. In this article, I have explained the complex science behind ‘Ridge Regression‘ and ‘Lasso Regression, ‘ which are the most fundamental regularization techniques used in data science, sadly still not used by many.

Learning Objectives

- Learn the concepts of Ridge and Lasso Regression and their role in regularizing linear regression models.

- Understand the differences between Ridge and Lasso regression, including the penalty term used in each approach and how it affects the regression model coefficients.

- Learn how to implement Ridge and Lasso Regression in Python using the scikit-learn library.

Table of contents

- What Are Ridge Regression and Lasso Regression?

- Why Penalize the Magnitude of Coefficients?

- How Does Ridge Regression Work?

- How Does Lasso Regression Work?

- Some Underlying Mathematical Principles

- Sample Project to Apply Your Regression Skills

- Comparison Between Ridge Regression and Lasso Regression

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Are Ridge Regression and Lasso Regression?

When we talk about regression, we often end up discussing Linear and Logistic Regression, as they are the most popular of the 7 types of regressions. In this article, we’ll focus on Ridge and Lasso regression, which are powerful techniques generally used for creating parsimonious models in the presence of a ‘large’ number of features. Here ‘large’ can typically mean either of two things:

- Large enough to enhance the tendency of a model to overfit (as low as 10 variables might cause overfitting)

- Large enough to cause computational challenges. With modern systems, this situation might arise in the case of millions or billions of features.

Though Ridge and Lasso might appear to work towards a common goal, the inherent properties and practical use cases differ substantially. If you’ve heard of them before, you must know that they work by penalizing the magnitude of coefficients of features and minimizing the error between predicted and actual observations. These are called ‘regularization’ techniques.

Lasso regression is a regularization technique. It is used over regression methods for a more accurate prediction. This model uses shrinkage. Shrinkage is where data values are shrunk towards a central point as the mean. The lasso procedure encourages simple, sparse models (i.e. models with fewer parameters).

Regularization Techniques

The key difference is in how they assign penalties to the coefficients:

- Ridge Regression:

- Performs L2 regularization, i.e., adds penalty equivalent to the square of the magnitude of coefficients

- Minimization objective = LS Obj + α * (sum of square of coefficients)

- Lasso Regression:

- Performs L1 regularization, i.e., adds penalty equivalent to the absolute value of the magnitude of coefficients

- Minimization objective = LS Obj + α * (sum of the absolute value of coefficients)

Here, LS Obj refers to the ‘least squares objective,’ i.e., the linear regression objective without regularization.

If terms like ‘penalty’ and ‘regularization’ seem very unfamiliar to you, don’t worry; we’ll discuss these in more detail throughout this article. Before digging further into how they work, let’s try to understand why penalizing the magnitude of coefficients should work in the first place.

Why Penalize the Magnitude of Coefficients?

Let’s try to understand the impact of model complexity on the magnitude of coefficients. As an example, I have simulated a sine curve (between 60° and 300°) and added some random noise using the following code:

Python Code

This resembles a sine curve but not exactly because of the noise. We’ll use this as an example to test different scenarios in this article. Let’s try to estimate the sine function using polynomial regression with powers of x from 1 to 15. Let’s add a column for each power upto 15 in our dataframe. This can be accomplished using the following code:

Add a Column for Each Power upto 15

for i in range(2,16): #power of 1 is already there

colname = 'x_%d'%i #new var will be x_power

data[colname] = data['x']**i

print(data.head())add a column for each power upto 15 The dataframe looks like this:

Making 15 Different Linear Regression Models

Now that we have all the 15 powers, let’s make 15 different linear regression models, with each model containing variables with powers of x from 1 to the particular model number. For example, the feature set of model 8 will be – {x, x_2, x_3, …, x_8}.

First, we’ll define a generic function that takes in the required maximum power of x as an input and returns a list containing – [ model RSS, intercept, coef_x, coef_x2, … upto entered power ]. Here RSS refers to the ‘Residual Sum of Squares,’ which is nothing but the sum of squares of errors between the predicted and actual values in the training data set and is known as the cost function or the loss function. The python code defining the function is:

#Import Linear Regression model from scikit-learn.

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

def linear_regression(data, power, models_to_plot):

#initialize predictors:

predictors=['x']

if power>=2:

predictors.extend(['x_%d'%i for i in range(2,power+1)])

#Fit the model

linreg = LinearRegression(normalize=True)

linreg.fit(data[predictors],data['y'])

y_pred = linreg.predict(data[predictors])

#Check if a plot is to be made for the entered power

if power in models_to_plot:

plt.subplot(models_to_plot[power])

plt.tight_layout()

plt.plot(data['x'],y_pred)

plt.plot(data['x'],data['y'],'.')

plt.title('Plot for power: %d'%power)

#Return the result in pre-defined format

rss = sum((y_pred-data['y'])**2)

ret = [rss]

ret.extend([linreg.intercept_])

ret.extend(linreg.coef_)

return retNote that this function will not plot the model fit for all the powers but will return the RSS and coefficient values for all the models. I’ll skip the details of the code for now to maintain brevity. I’ll be happy to discuss the same through the comments below if required.

Store all the Results in Pandas Dataframe

Now, we can make all 15 models and compare the results. For ease of analysis, we’ll store all the results in a Pandas dataframe and plot 6 models to get an idea of the trend. Consider the following code:

#Initialize a dataframe to store the results:

col = ['rss','intercept'] + ['coef_x_%d'%i for i in range(1,16)]

ind = ['model_pow_%d'%i for i in range(1,16)]

coef_matrix_simple = pd.DataFrame(index=ind, columns=col)

#Define the powers for which a plot is required:

models_to_plot = {1:231,3:232,6:233,9:234,12:235,15:236}

#Iterate through all powers and assimilate results

for i in range(1,16):

coef_matrix_simple.iloc[i-1,0:i+2] = linear_regression(data, power=i, models_to_plot=models_to_plot)We would expect the models with increasing complexity to better fit the data and result in lower RSS values. This can be verified by looking at the plots generated for 6 models:

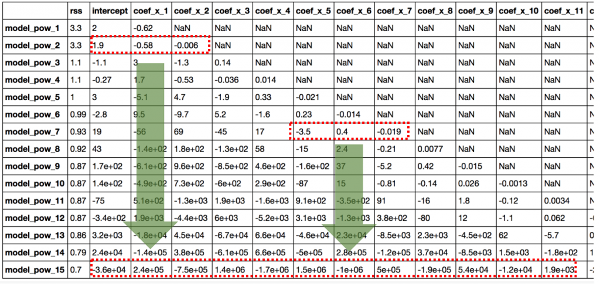

This clearly aligns with our initial understanding. As the model complexity increases, the models tend to fit even smaller deviations in the training data set. Though this leads to overfitting, let’s keep this issue aside for some time and come to our main objective, i.e., the impact on the magnitude of coefficients. This can be analyzed by looking at the data frame created above.

Python Code

#Set the display format to be scientific for ease of analysis

pd.options.display.float_format = '{:,.2g}'.format

coef_matrix_simpleThe output looks like this:

It is clearly evident that the size of coefficients increases exponentially with an increase in model complexity. I hope this gives some intuition into why putting a constraint on the magnitude of coefficients can be a good idea to reduce model complexity.

Let’s try to understand this even better.

What does a large coefficient signify? It means that we’re putting a lot of emphasis on that feature, i.e., the particular feature is a good predictor for the outcome. When it becomes too large, the algorithm starts modeling intricate relations to estimate the output and ends up overfitting the particular training data.

I hope the concept is clear. Now, let’s understand ridge and lasso regression in detail and see how well they work for the same problem.

How Does Ridge Regression Work?

As mentioned before, ridge regression performs ‘L2 regularization‘, i.e., it adds a factor of the sum of squares of coefficients in the optimization objective. Thus, ridge regression optimizes the following:

Objective = RSS + α * (sum of the square of coefficients)

Here, α (alpha) is the parameter that balances the amount of emphasis given to minimizing RSS vs minimizing the sum of squares of coefficients. α can take various values:

- α = 0:

- The objective becomes the same as simple linear regression.

- We’ll get the same coefficients as simple linear regression.

- α = ∞:

- The coefficients will be zero. Why? Because of infinite weightage on the square of coefficients, anything less than zero will make the objective infinite.

- 0 < α < ∞:

- The magnitude of α will decide the weightage given to different parts of the objective.

- The coefficients will be somewhere between 0 and ones for simple linear regression.

I hope this gives some sense of how α would impact the magnitude of coefficients. One thing is for sure – any non-zero value would give values less than that of simple linear regression. By how much? We’ll find out soon. Leaving the mathematical details for later, let’s see ridge regression in action on the same problem as above.

Function for Ridge Regression

First, let’s define a generic function for ridge regression similar to the one defined for simple linear regression. The Python code is:

from sklearn.linear_model import Ridge

def ridge_regression(data, predictors, alpha, models_to_plot={}):

#Fit the model

ridgereg = Ridge(alpha=alpha,normalize=True)

ridgereg.fit(data[predictors],data['y'])

y_pred = ridgereg.predict(data[predictors])

#Check if a plot is to be made for the entered alpha

if alpha in models_to_plot:

plt.subplot(models_to_plot[alpha])

plt.tight_layout()

plt.plot(data['x'],y_pred)

plt.plot(data['x'],data['y'],'.')

plt.title('Plot for alpha: %.3g'%alpha)

#Return the result in pre-defined format

rss = sum((y_pred-data['y'])**2)

ret = [rss]

ret.extend([ridgereg.intercept_])

ret.extend(ridgereg.coef_)

return retNote the ‘Ridge’ function used here. It takes ‘alpha’ as a parameter on initialization. Also, keep in mind that normalizing the inputs is generally a good idea in every type of regression and should be used in the case of ridge regression as well.

Now, let’s analyze the result of Ridge regression for 10 different values of α ranging from 1e-15 to 20. These values have been chosen so that we can easily analyze the trend with changes in values of α. These would, however, differ from case to case.

Note that each of these 10 models will contain all the 15 variables, and only the value of alpha would differ. This differs from the simple linear regression case, where each model had a subset of features.

Python Code

#Initialize predictors to be set of 15 powers of x

predictors=['x']

predictors.extend(['x_%d'%i for i in range(2,16)])

#Set the different values of alpha to be tested

alpha_ridge = [1e-15, 1e-10, 1e-8, 1e-4, 1e-3,1e-2, 1, 5, 10, 20]

#Initialize the dataframe for storing coefficients.

col = ['rss','intercept'] + ['coef_x_%d'%i for i in range(1,16)]

ind = ['alpha_%.2g'%alpha_ridge[i] for i in range(0,10)]

coef_matrix_ridge = pd.DataFrame(index=ind, columns=col)

models_to_plot = {1e-15:231, 1e-10:232, 1e-4:233, 1e-3:234, 1e-2:235, 5:236}

for i in range(10):

coef_matrix_ridge.iloc[i,] = ridge_regression(data, predictors, alpha_ridge[i], models_to_plot)This would generate the following plot:

Here we can clearly observe that as the value of alpha increases, the model complexity reduces. Though higher values of alpha reduce overfitting, significantly high values can cause underfitting as well (e.g., alpha = 5). Thus alpha should be chosen wisely. A widely accepted technique is cross-validation, i.e., the value of alpha is iterated over a range of values, and the one giving a higher cross-validation score is chosen.

Let’s have a look at the value of coefficients in the above models:

Python Code

#Set the display format to be scientific for ease of analysis

pd.options.display.float_format = '{:,.2g}'.format

coef_matrix_ridgeThis straight away gives us the following inferences:

- The RSS increases with an increase in alpha.

- An alpha value as small as 1e-15 gives us a significant reduction in the magnitude of coefficients. How? Compare the coefficients in the first row of this table to the last row of the simple linear regression table.

- High alpha values can lead to significant underfitting. Note the rapid increase in RSS for values of alpha greater than 1

- Though the coefficients are really small, they are NOT zero.

The first 3 are very intuitive. But #4 is also a crucial observation. Let’s reconfirm the same by determining the number of zeros in each row of the coefficients data set:

Python Code

coef_matrix_ridge.apply(lambda x: sum(x.values==0),axis=1)This confirms that all 15 coefficients are greater than zero in magnitude (can be +ve or -ve). Remember this observation and have a look again until it’s clear. This will play an important role later while comparing ridge with lasso regression.

How Does Lasso Regression Work?

LASSO stands for Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator. I know it doesn’t give much of an idea, but there are 2 keywords here – ‘absolute‘ and ‘selection. ‘

Let’s consider the former first and worry about the latter later.

Lasso regression performs L1 regularization, i.e., it adds a factor of the sum of the absolute value of coefficients in the optimization objective. Thus, lasso regression optimizes the following:

Objective = RSS + α * (sum of the absolute value of coefficients)

Here, α (alpha) works similar to that of the ridge and provides a trade-off between balancing RSS and the magnitude of coefficients. Like that of the ridge, α can take various values. Let’s iterate it here briefly:

- α = 0: Same coefficients as simple linear regression

- α = ∞: All coefficients zero (same logic as before)

- 0 < α < ∞: coefficients between 0 and that of simple linear regression

Defining Generic Function

Yes, its appearing to be very similar to Ridge till now. But hang on with me, and you’ll know the difference by the time we finish. Like before, let’s run lasso regression on the same problem as above. First, we’ll define a generic function:

from sklearn.linear_model import Lasso

def lasso_regression(data, predictors, alpha, models_to_plot={}):

#Fit the model

lassoreg = Lasso(alpha=alpha,normalize=True, max_iter=1e5)

lassoreg.fit(data[predictors],data['y'])

y_pred = lassoreg.predict(data[predictors])

#Check if a plot is to be made for the entered alpha

if alpha in models_to_plot:

plt.subplot(models_to_plot[alpha])

plt.tight_layout()

plt.plot(data['x'],y_pred)

plt.plot(data['x'],data['y'],'.')

plt.title('Plot for alpha: %.3g'%alpha)

#Return the result in pre-defined format

rss = sum((y_pred-data['y'])**2)

ret = [rss]

ret.extend([lassoreg.intercept_])

ret.extend(lassoreg.coef_)

return retNotice the additional parameters defined in the Lasso function – ‘max_iter. ‘ This is the maximum number of iterations for which we want the model to run if it doesn’t converge before. This exists for Ridge as well, but setting this to a higher than default value was required in this case. Why? I’ll come to this in the next section.

Different Values of Alpha

Let’s check the output for 10 different values of alpha using the following code:

#Initialize predictors to all 15 powers of x

predictors=['x']

predictors.extend(['x_%d'%i for i in range(2,16)])

#Define the alpha values to test

alpha_lasso = [1e-15, 1e-10, 1e-8, 1e-5,1e-4, 1e-3,1e-2, 1, 5, 10]

#Initialize the dataframe to store coefficients

col = ['rss','intercept'] + ['coef_x_%d'%i for i in range(1,16)]

ind = ['alpha_%.2g'%alpha_lasso[i] for i in range(0,10)]

coef_matrix_lasso = pd.DataFrame(index=ind, columns=col)

#Define the models to plot

models_to_plot = {1e-10:231, 1e-5:232,1e-4:233, 1e-3:234, 1e-2:235, 1:236}

#Iterate over the 10 alpha values:

for i in range(10):

coef_matrix_lasso.iloc[i,] = lasso_regression(data, predictors, alpha_lasso[i], models_to_plot)This gives us the following plots:

This again tells us that the model complexity decreases with an increase in the values of alpha. But notice the straight line at alpha=1. Appears a bit strange to me. Let’s explore this further by looking at the coefficients:

Apart from the expected inference of higher RSS for higher alphas, we can see the following:

- For the same values of alpha, the coefficients of lasso regression are much smaller than that of ridge regression (compare row 1 of the 2 tables).

- For the same alpha, lasso has higher RSS (poorer fit) as compared to ridge regression.

- Many of the coefficients are zero, even for very small values of alpha.

Inferences #1 and 2 might not always generalize but will hold for many cases. The real difference from the ridge is coming out in the last inference. Let’s check the number of coefficients that are zero in each model using the following code:

coef_matrix_lasso.apply(lambda x: sum(x.values==0),axis=1)We can observe that even for a small value of alpha, a significant number of coefficients are zero. This also explains the horizontal line fit for alpha=1 in the lasso plots; it’s just a baseline model! This phenomenon of most of the coefficients being zero is called ‘sparsity. ‘ Although lasso performs feature selection, this level of sparsity is achieved in special cases only, which we’ll discuss towards the end.

This has some really interesting implications on the use cases of lasso regression as compared to that of ridge regression. But before coming to the final comparison, let’s take a bird’s eye view of the mathematics behind why coefficients are zero in the case of lasso but not ridge.

Python Code

Some Underlying Mathematical Principles

Here’s a sneak peek into some of the underlying mathematical principles of regression. If you wish to get into the details, I recommend taking a good statistics textbook, like Elements of Statistical Learning.

Let’s start by reviewing the basic structure of data in a regression problem.

In this infographic, you can see there are 4 data elements:

- X: the matrix of input features (nrow: N, ncol: M+1)

- Y: the actual outcome variable (length:N)

- Yhat: these are predicted values of Y (length:N)

- W: the weights or the coefficients (length: M+1)

Here, N is the total number of data points available, and M is the total number of features. X has M+1 columns because of M features and 1 intercept.

The predicted outcome for any data point i is:

It is simply the weighted sum of each data point with coefficients as the weights. This prediction is achieved by finding the optimum value of weights based on certain criteria, which depends on the type of regression algorithm being used. Let’s consider all 3 cases:

Simple Linear Regression

The objective function (also called the cost) to be minimized is just the RSS (Residual Sum of Squares), i.e., the sum of squared errors of the predicted outcome as compared to the actual outcome. This can be depicted mathematically as:

In order to minimize this cost, we generally use a ‘gradient descent’ algorithm. The overall algorithm works like this:

1. initialize weights (say w=0)

2. iterate till not converged

2.1 iterate over all features (j=0,1...M)

2.1.1 determine the gradient

2.1.2 update the jth weight by subtracting learning rate times the gradient

w(t+1) = w(t) - learning rate * gradientHere the important step is #2.1.1, where we compute the gradient. A gradient is nothing but a partial differential of the cost with respect to a particular weight (denoted as wj). The gradient for the jth weight will be:

This is formed from 2 parts:

- 2*{..}: This is formed because we’ve differentiated the square of the term in {..}

- -wj: This is the differentiation of the part in {..} wrt wj. Since it’s a summation, all others would become 0, and only wj would remain.

Step #2.1.2 involves updating the weights using the gradient. This updating step for simple linear regression looks like this:

Note the +ve sign in the RHS is formed after the multiplication of 2 -ve signs. I would like to explain point #2 of the gradient descent algorithm mentioned above, ‘iterate till not converged.‘ Here convergence refers to attaining the optimum solution within the pre-defined limit.

It is checked using the value of the gradient. If the gradient is small enough, it means we are very close to the optimum, and further iterations won’t substantially impact the coefficients. The lower limit on the gradient can be changed using the ‘tol‘ parameter.

Let’s consider the case of ridge regression now.

Ridge Regression

The objective function (also called the cost) to be minimized is the RSS plus the sum of squares of the magnitude of weights. This can be depicted mathematically as:

In this case, the gradient would be:

Again in the regularization part of a gradient, only wj remains, and all others would become zero. The corresponding update rule is:

Here we can see that the second part of the RHS is the same as that of simple linear regression. Thus, ridge regression is equivalent to reducing the weight by a factor of (1-2λη) first and then applying the same update rule as simple linear regression. I hope this explains why the coefficients get reduced to small numbers but never become zero.

Note that the criteria for convergence, in this case, remains similar to simple linear regression, i.e., checking the value of gradients. Let’s discuss Lasso regression now.

Lasso Regression

The objective function (also called the cost) to be minimized is the RSS plus the sum of the absolute value of the magnitude of weights. This can be depicted mathematically as:

In this case, the gradient is not defined as the absolute function is not differentiable at x=0. This can be illustrated as:

We can see that the parts on the left and right sides of 0 are straight lines with defined derivates, but the function can’t be differentiated at x=0. In this case, we have to use a different technique called coordinate descent, which is based on the concept of sub-gradients. One of the coordinate descent follows the following algorithms (this is also the default in sklearn):

1. initialize weights (say w=0)

2. iterate till not converged

2.1 iterate over all features (j=0,1...M)

2.1.1 update the jth weight with a value which minimizes the cost#2.1.1 might look too generalized. But I’m intentionally leaving the details and jumping to the update rule:

Sample Project to Apply Your Regression Skills

Problem Statement

Demand forecasting is a key component of every growing online business. Without proper demand forecasting processes in place, it can be nearly impossible to have the right amount of stock on hand at any given time. A food delivery service has to deal with a lot of perishable raw materials, which makes it all the more important for such a company to accurately forecast daily and weekly demand.

Too much inventory in the warehouse means more risk of wastage, and not enough could lead to out-of-stocks — and push customers to seek solutions from your competitors. In this challenge, get a taste of the demand forecasting challenge using a real dataset.

Difference Between Actual and Predicted Outcome

Here g(w-j) represents (but not exactly) the difference between the actual outcome and the predicted outcome considering all EXCEPT the jth variable. If this value is small, it means that the algorithm is able to predict the outcome fairly well even without the jth variable, and thus it can be removed from the equation by setting a zero coefficient. This gives us some intuition into why the coefficients become zero in the case of lasso regression.

In coordinate descent, checking convergence is another issue. Since gradients are not defined, we need an alternate method. Many alternatives exist, but the simplest one is to check the step size of the algorithm. We can check the maximum difference in weights in any particular cycle overall feature weights (#2.1 of the algorithm above).

If this is lower than the specified ‘tol,’ the algorithm will stop. The convergence is not as fast as the gradient descent. If a warning appears saying that the algorithm stopped before convergence, we might have to set the ‘max_iter’ parameter. This is why I specified this parameter in the Lasso generic function.

Let’s summarize our understanding by comparing the coefficients in all the three cases using the following visual, which shows how the ridge and lasso coefficients behave in comparison to the simple linear regression case.

Reinforced Facts

Apologies for the lack of visual appeal. But I think it is good enough to re-inforced the following facts:

- The ridge coefficients are a reduced factor of the simple linear regression coefficients and thus never attain zero values but very small values.

- The lasso coefficients become zero in a certain range and are reduced by a constant factor, which explains their low magnitude in comparison to the ridge.

Before going further, one important issue in the case of both ridge and lasso regression is intercept handling. Generally, regularizing the intercept is not a good idea and should be left out of regularization. This requires slight changes in the implementation, which I’ll leave you to explore.

Comparison Between Ridge Regression and Lasso Regression

Now that we have a fair idea of how ridge and lasso regression work, let’s try to consolidate our understanding by comparing them and appreciating their specific use cases. I will also compare them with some alternate approaches. Let’s analyze these under three buckets:

Key Difference

- Ridge: It includes all (or none) of the features in the model. Thus, the major advantage of ridge regression is coefficient shrinkage and reducing model complexity.

- Lasso: Along with shrinking coefficients, the lasso also performs feature selection. (Remember the ‘selection‘ in the lasso full-form?) As we observed earlier, some of the coefficients become exactly zero, which is equivalent to the particular feature being excluded from the model.

Traditionally, techniques like stepwise regression were used to perform feature selection and make parsimonious models. But with advancements in Machine-Learning, ridge and lasso regressions provide very good alternatives as they give much better output, require fewer tuning parameters, and can be automated to a large extent.

Typical Use Cases

- Ridge: It is majorly used to prevent overfitting. Since it includes all the features, it is not very useful in the case of exorbitantly high #features, say in millions, as it will pose computational challenges.

- Lasso: Since it provides sparse solutions, it is generally the model of choice (or some variant of this concept) for modeling cases where the #features are in millions or more. In such a case, getting a sparse solution is of great computational advantage as the features with zero coefficients can be ignored.

It’s not hard to see why the stepwise selection techniques become practically cumbersome to implement in high-dimensionality cases. Thus, the lasso provides a significant advantage.

Presence of Highly Correlated Features

- Ridge: It generally works well even in the presence of highly correlated features, as it will include all of them in the model. Still, the coefficients will be distributed among them depending on the correlation.

- Lasso: It arbitrarily selects any feature among the highly correlated ones and reduces the coefficients of the rest to zero. Also, the chosen variable changes randomly with changes in model parameters. This generally doesn’t work that well as compared to ridge regression.

This disadvantage of the lasso can be observed in the example we discussed above. Since we used a polynomial regression, the variables were highly correlated. (Not sure why? Check the output of data.corr() ). Thus, we saw that even small values of alpha were giving significant sparsity (i.e., high #coefficients as zero).

Along with Ridge and Lasso, Elastic Net is another useful technique that combines both L1 and L2 regularization. It can be used to balance out the pros and cons of ridge and lasso regression. I encourage you to explore it further.

Conclusion

In this article, we got an overview of regularization using ridge and lasso regression. We then found out why penalizing the magnitude of coefficients should give us parsimonious models. Next, we went into details of ridge and lasso regression and saw their advantages over simple linear regression. We also understood how and why they should work. We also peeked into the mathematical part of the regressions.

Regularization techniques are really useful, and I encourage you to implement them. If you’re ready to take the challenge, you must try them on the BigMart Sales Prediction problem discussed at the beginning of this article.

Key Takeaways

- Ridge and Lasso Regression are regularization techniques used to prevent overfitting in linear regression models by adding a penalty term to the loss function.

- In Python, scikit-learn provides easy-to-use functions for implementing Ridge and Lasso regression with hyperparameter tuning and cross-validation.

- Ridge regression can handle multicollinearity in the input data by reducing the impact of correlated features on the coefficients, while Lasso regression automatically selects the most important features for prediction.

Frequently Asked Questions

A. Ridge and Lasso Regression are regularization techniques in machine learning. Ridge adds L2 regularization, and Lasso adds L1 to linear regression models, preventing overfitting.

A. Use Ridge when you have many correlated predictors and want to avoid multicollinearity. Use Lasso when feature selection is crucial or when you want a sparse model.

A. Ridge Regression adds a penalty term proportional to the square of the coefficients, while Lasso adds a penalty term proportional to the absolute value of the coefficients, which can lead to variable selection.

A. Ridge and Lasso are used to prevent overfitting in regression models by adding regularization terms to the cost function, encouraging simpler models with fewer predictors and more generalizability.